Botanic Sojourn

Scott Zona, Ph.D. Former Palm Biologist

Photographs by author unless noted

|

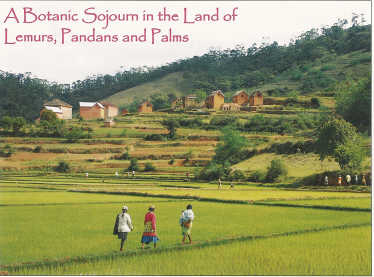

| Rice paddies in central Madagascar near Antsirabe |

Madagascar is a biological hotspot, with hundreds of species of plants found nowhere else in the world. Some 80% of the plants are endemic (found nowhere else), and for animals, such as lemurs and chameleons, the percentage is as high as 90%. It is truly a must-see destination for any biologist. When offered the opportunity to join a team of botanists from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Missouri Botanical Garden; the University of Antananarivo, Madagascar; and the Tsimbazaza Botanical and Zoological Park, Madagascar, I jumped at the chance. A three-week visit is nowhere near long enough to gain a full appreciation for Madagascar's biological diversity, but at least I could sample its offerings.

Our team consisted of Drs. John Dransfield, Soejatmi Dransfield and Adam Britt of Kew. John literally wrote the book on the palms of Madagascar; while Soejatmi is the world authority on the island's bamboos. Adam is a lemur specialist, who now heads Kew's threatened plant program for Madagascar. Kew's in-country project coordinator, Tianjanahary Randriamboavonjy, and a university student, Mijoro Rakotoarinivo, accompanied us. Jimmy Razafitsalama, Missouri's field collector, and Rolland Ranaivojaoan and Ranta Razafindraibe, both of Tsimbazaza, also joined us in the field.

|

| One of the many ferry crossings. Most ferries are not motorized; the crossing is made by pulling the ferry along the rope stretched across the river. |

Our purpose for the trip was two-fold: We were assessing projects and sites for Kew's conservation efforts and directing Mijoro's thesis project, which involves palm conservation assessment. I was there to work with the Kew team in making collections, which will be deposited in Fairchild's herbarium and DNA bank, and to make arrangements for acquiring seeds.

|

| Dypsis louvelii is a small forest palm with simple, corrugated leaves. |

My first impression of Madagascar was that Kew's conservation efforts come not a moment too soon. Vast areas have been deforested and burned; they are now eroded and barren grasslands. I was surprised to see that the famous traveler's tree, Ravenala madagascariensis, is a dreadful weed and a good indicator of disturbed vegetation. Rice cultivation is tremendously important, and vast areas of land have been converted to paddy rice culture. The intricate systems of irrigation canals and terraces, while picturesque, are reminders of the devastation visited upon the forests.

|

| Ravenala madagascariensis, a relative of the banana,

is endemic to Madagascar where it favors disturbed valley bottoms.

Denuded hillside in the background once supported lowland rainforest. |

Despite the destruction, large areas of forest remain where Malagasy specialties abound. Palm lovers know Madagascar as home to the genus Dypsis; in three weeks, we saw more than 20 species in the wild. The genus is incredibly diverse in terms of habit, from the giant D. prestoniana, which emerges through the forest canopy, to tiny D. tenuissima, possibly the world's smallest palm. Its trunk is only an eighth of an inch in diameter, and a fully-grown specimen only knee high. It seemed that every remnant of montane rainforest, coastal forest or spiny forest had its own species of Dypsis.

|

| The improbable Ravenea musicalis - emergent adults and trunkless juveniles are visible above. |

We also saw several species of Madagascar's native genus Ravenea. In the southeast, two rivers within a few miles of each other are home to two of Madagascar's most remarkable palms. One is the impressive Ravenea musicalis, a palm unknown to science until it was discovered by Henk Beentje, co-author of The Palms of Madagascar, during the course of Kew's eponymus project. R. musicalis, named for the musical sound of its fruits plip-plopping into the river, germinates underwater and grows totally submerged for several years. Eventually, seedlings emerge and grow into enormous palms looking like they had waded into the water by mistake.

|

| The delicate Dypsis aquatalis, an aquatic palm |

|

| Our team collecting specimens of Dypsis aquatalis. Right to left: Razafitsalama, T Randriamboavonjy holding specimens, S. Zona, Dransfield kneeling, S. Dransfield, G. Rakotondranony kneeling, and two drivers. |

Dypsis aquatalis was also unknown until Beentje described the species from a single dried specimen in the Paris herbarium. This was the first time any of us had seen living plants of this species. D. aquatalis is a small palm, which grows with its roots and stems submerged; only the graceful pinnate leaves are held high and dry. We found this species after many hours of driving along excruciatingly poor roads and several time-consuming ferry crossings. When we stopped to see if a broken-down bridge would support our vehicles, John serendipitously spotted the palm growing in a thicket of Pandanus and Typhonodorum (a genus of aquatic aroids endemic to Madagascar).

|

| Pandanus platyphyllus, one of the many strange and wonderful Pandanaceae endemic to Madagascar |

The genus Pandanus has tremendous diversity in Madagascar, and every day I begged our driver to pull over so that I could photograph yet another strange pandan. We saw enormous forest pandans, coniferoid pandans (which look like Araucaria from a distance), aquatic pandans, and the marvelous Pandanus platyphyllus, which lined streams and rivers in the south. I came away from Madagascar with a renewed appreciation for the Pandanaceae and a desire to see more species in cultivation at the Garden.

|

| A black-and-white ruffed lemur (Varecia variegata variegata) was unperturbed by our presence just a few feet below its resting spot. |

We were thrilled to see many of Madagascar's renowned orchids in the wild. In a forest fragment in the south we saw what was for me the most exciting of these orchids: a specimen of Angraecum sesquipedale in full bloom. This orchid is famous for its extraordinarily long nectar spur. Charles Darwin himself predicted that a moth must exist with a proboscis long enough to reach the nectar and yes, some years later such a moth was discovered. Seeing the orchid that was the subject of such a famous prediction by one of science's greatest luminaries was one of the highlights of the expedition.

|

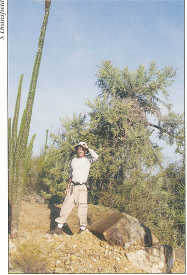

| The author flanked by two Malagasy endemics, Alluaudia procera of the endemic family Didiereaceae (left) and a spiny Euphorbia stenoclada (right). |

During our final days on the trip, I visited one of Madagascar's most interesting forest types, the spiny forest in Adohahela National Park. The park is home to vast areas of dry forest, dominated by spiny plants and succulents. I was particularly gratified to see two species of Alluaudia of the endemic Didiereaceae. These strange plants are the Malagasy analogs of a genus of plants I know from the deserts of California and Arizona, Fouquieria, of the Fouquieriaceae. The two families, completely unrelated, are textbook examples of convergent evolution, the idea that similar selective forces (in this case, extreme drought) can mold plants into similar morphologies.

My brief time in Madagascar was well worth the effort of getting there. We accomplished the goals of our expedition, and I came away with a feeling for the unique plant life of that island. More importantly, I made good friends among the thriving, young botanic community in Madagascar. In those young botanists, there may yet be hope for the conservation of the island's plants.

Garden Views Spring 2004