Cocos Island

Jennifer Trusty, Ph.D.

|

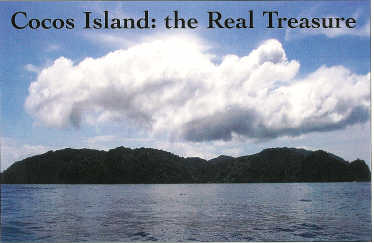

| Cocos Island, a haven for rare and endangered plants, is a welcome sight after 36 hours at sea! |

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden has long been known for plant exploration and collection. Soon after the Garden was founded, David Fairchild set sail with family and friends on the Cheng Ho, a Chinese junk, to collect plants throughout the Philippines and the Indonesian archipelago. Some sixty-odd years later, Dr. Fairchild's passion for plant exploration and collection lives on in the Fairchild scientists who travel throughout the world to add to our knowledge of tropical plants. As a Florida International University graduate student working at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, I have followed my passion to a remote, uninhabited Pacific island called Isla del Coco, or Cocos Island, where I conducted my dissertation research.

|

| Chatham Bay is still the resting place of many ocean travelers. |

My quest to study the flora of Cocos Island began while I was taking a graduate course in Plant Systematics in Costa Rica sponsored by the Organization for Tropical Studies COTS). After identifying and studying plants in many dlfferent ecosystems throughout Costa Rica, I was surprised by the lack of information for Cocos Island and my interest was piqued by the oft-repeated declaration, “There must be a lot of new plants out there.” This was exactly the opportunity I had dreamed of.

With advice and support from my advisor, Dr. Javier Francisco-Ortega, a warm welcome from the Cocos Island National Park and the financial backing of OTS, FIU and the United States Environmental Ptotection Agency, I traveled to the island in July, 2001. Although at times it may seem the world has gotten too small and too well known, there are still a few remote, lonely places that remain untamed by humans. Cocos Island is one of them. Located 350 miles southwest of Costa Rica, it is the only exposed island in a chain of volcanic seamounts called the Cocos Ridge.

|

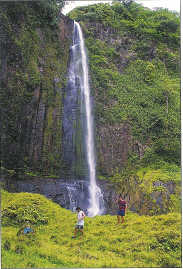

| Iglesias waterfall is one of the spectaular waterfalls on Cocos Island. |

The island is small — less than ten square miles — but has an extremely rugged terrain. Cocos Island receives a spectacular amount of rain each year, nearly 21 feet. That rain pours into an abundance of rivers that cascade off the high cliffs of the island into the sea. It also supports the dense vegetation that gives the island its lush, green appearance.

The island's remote location and steep, densely-forested terrain have contributed to its remaining largely uninhabited throughout its known history. In the past, it was frequented by notorious pirates who were said to have buried their treasure there, although none has ever been found. The most famous hoard rumored to be on the island, “The Treasure of Lima,” has been valued as high as 60 million dollars. It was stolen by Captain William Thompson of the Mary Dear in 1821. Today the Costa Rican Park Service stations about ten park guards on the island for the protection of both the marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

|

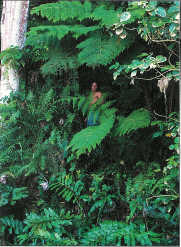

| Cyathea nesiotica is one of the tree ferns endemic to Cocos Island. |

Although Cocos is best known for its teeming marine life, my research focused on the diversity of vascular plants in the forested interior of the island. The island is gorgeous, but it is also a physically challenging place to work. Herbert “Tug” Kesler, a fellow researcher, and I spent a total of 14 weeks on the island between July 2001 and December 2002. While there, we made more than 500 individual collections of plants. Our three trips to the island were distributed between the wet and less wet seasons to maximize our opportunity to collect reproductive plants. We collected on foot, from kayaks and by boat. These collections represent the largest number of plant species collected from Cocos Island and will add more than 100 new records to the previous plant list for a total of more than 250 vascular plant species. The collections will be housed at the Museo Nacional in Costa Rica and the Fairchild Tropical Garden Herbarium.

In addition, at least two species that are new to science will be described from the collections we made. These new species are in the families Orchidaceae and Melastomataceae.

|

| Tug collected many beautiful plants on Cocos Island. |

Many unique plants on islands are endemic, i.e., only found in that single location. Because of the small population and restricted range of these plants, they have a high priority for conservation. Although Cocos Island is both a protected national park and a World Conservation Union (IUCN) World Heritage Site, the presence of feral pigs, deer and rats endanger these unique species. I hope to aid in the conservation of the plants of Cocos Island by identifying and mapping rare species for the park. This information will help them with future planning and development. Also, by determining and listing the IUCN conservation status for Cocos Island plants, I hope to focus research and conservation efforts on the island.

|

| The author climbs high in a tree to collect epiphytes. |

One of the most interesting questions to ask about island plants is where and how they arrived. The study of the geographical pattern of species is called biogeography. For my dissertation work, I am studying the biogeographic relationships of the endemic species of tree ferns (Cyathea) and orchids (Epidendrum) found on Cocos Island. In addition to collecting herbarium specimens, we also collected samples to undergo DNA analysis in the joint FIU/FTG Molecular Systematics Laboratory at Fairchild's Research Center. I hope to learn where the relatives of these endemic species originated. I am especially interested in discovering if the endemic species in these groups are the result of a single dispersal event followed by speciation or if these species have colonized independently of one another.

The time I spent working on Cocos Island has been an incredible experience. I endured seasickness for the 36-hour boat ride, maneuvered a kayak through waves onto ??? beaches, slid down cliffs, camped under falling stars and fled out of the water after encountering many, many sharks. Although I never saw a trace of the pirates' treasure, I did see previously unknown plants in one of the most beautiful wild places left on this earth. I am lucky to have had this opportunity and would encourage anyone who dreams of far-off plants to “Go explore!”

Garden Views Spring 2003