|

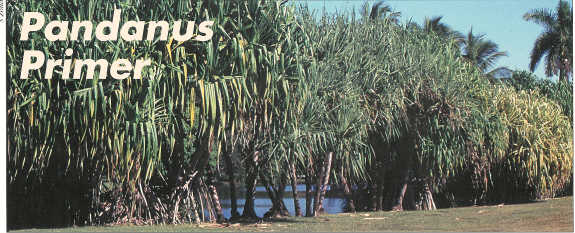

| Several species of Pandanus fringe Pandanus Lake |

Pandanus Primer

Scott Zona, Ph.D., Former Palm Biologist

| ||

| Stilt roots allow Pandanus to grow in muddy, unstable and anaerobic habitats. | The sharp teeth on this species of Pandanus keep friends and foe at bay. | The three-ranked leaves of Pandanus give it its common name, screw pine. |

In the lowlands of the Garden, along Pandanus Lake (plots 61 and 62), visitors can see a portion of the Garden's Pandanus collection. Pandanus, one of three genera that make up the Pandanaceae, is a tropical group, restricted to the Eastern Hemisphere, from Africa to the islands of the Pacific. They may occasionally grow as shrubs or epiphytes, but most Pandanus in cultivation are trees. Some unique species from Madagascar resemble Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine) in their habit of growth. Others resemble palms, aloes, Dracaena or Cordyline in their growth habit, but Pandanus is not closely related to any of these other plants.

|

| A single Pandanus spreads its branches in the Lowlands. |

Visitors seeing a Pandanus for the first time are likely to notice two striking features: its roots and its leaves. Looking like dragon trees wading in the shallows while trying to avoid getting their feet wet, a group of Pandanus along a shoreline is an impenetrable tangle of thick, woody roots topped off by tufts of strap-shaped leaves. They are a formidable presence along Pandanus Lake, just as they are in the wild. Visitors quickly appreciate why Pandanus is such a challenge for tropical botanists.

|

| Fruits of Pandanus are often bright and colorful but inedibiy fibrous. The individual segments of the fruits break off and are dispersed singly |

In the wild, Pandanus grows in forests, riverbanks, and along coastlines, but it is at its best in unstable habitats, where its roots are able to capture and hold shifting sediments.

|

| It's easy to see where the name "screw pine" came from. |

Like our red mangroves, Pandanus has conspicuous prop roots which emerge above the soil/water line and arch away from the stem, curving gracefully toward the ground. These prop roots stabilize over-reaching plants, especially in areas subject to water erosion. Once the prop roots grow into the soil, they branch and transform into conventional water- and nutrient-absorbing roots. The aerial roots also conduct air to the roots that are buried deep within the suffocating mud and silt. Some species, such as P. solms-laubachii (plot 170), also produce negatively geotropic roots on their stem. These roots grow away from the earth, rather than down toward it, and stand up along the stem like bristles on a brush. Their function is poorly understood.

Visitors are advised to make the acquaintance of the long, strappy leaves from a discreet distance. Up close, the need for caution is apparent. The leaves are cunningly armed with small but sharp teeth along each leaf margin, with a third row of teeth on the underside of the midvein. Leaves are arranged in three ranks, which spiral around the stem like the thread of a screw. A common name, screw pine, comes from the spiral leaf arrangement and the fruits that resemble pineapples. That resemblance is only skin-deep.

The leaves of Pandanus are put to use throughout the Pacific (once the rows of teeth have been removed). In Polynesian cultures, they are the preferred material for weaving fine mats and are also used for hats, baskets, thatch, etc. Some leaves are retted for fibers and used for cordage.

Visitors to Plot 83 are likely to smell Pandanus amaryllifolius even before they see it. The leaves of P. amaryllifolius are used to impart a distinctive musty or nutty flavor to rice and sugar. This species derives its aroma from 2-acetyl-l-pyrroline, a chemical which occurs naturally in the leaves of this Pandanus as well as in the grains of some strains of basamati rice.

Pandanus plants are dioecious, i.e., male and female flowers are produced on separate plants. Creamy white male (staminate) flowers are produced in long clusters that dangle from the tips of branches. They bloom in summer and produce light, windborne pollen: tapping a cluster releases a cloud of pollen. Female (pistillate) flowers are borne in tight, spherical heads the size of softballs. In full bloom, they are rather drab, although the flowers of a sister of Pandanus, the genus Freycinetia, often have brightly colored bracts cupped around the smaller heads of flowers. The colored bracts attract birds and bats, which are the pollinators, to the inflorescences of Freycinetia.

The female flowers coalesce in fruit, and the single fruit that results is classified as a multiple fruit. The multiple fruits of some species betray their origins when they ripen and fall apart into single-seeded sections called "keys." Ripe fruits of many species are bright scarlet and have a pleasant, fruity aroma, but they are extremely fibrous. Visitors are advised not to eat the fruits. One may well expend more calories chewing the fruits than one would gain by digesting them. The seeds of some species are prized as a source of edible oil and are gathered for that purpose. In the wild, animals disperse the forest-dwelling species, while the seeds of coastal species are dispersed by water.

Some Pandanus species are apomictic, meaning that females form fruits and seeds without benefit of males. It is botanical virgin birth. In fact, some Pandanus species are known only by their female plants; males have never been found. Isolated female plants in cultivation may produce fruits, and female inflorescences bagged to exclude wind-borne pollen produce fruits just as pollinated flowers do. This form of asexual reproduction produces offspring that are almost always genetically identical to the mother. Hence, offspring are well suited to the environment of their mother but are less likely to succeed in new environments. Apomixis and its effects on the genetic structure of a population may explain how so many species of Pandanus evolved (approximately 700 species) and their tendency to be restricted to narrow geographic areas.

Sadly, many of the world's Pandanus are threatened in the wild. They cannot survive when their homelands are destroyed. Species restricted to a small area have nowhere to go when that area is lost. Several species endemic to Mauritius, the home of the dodo, have gone the way of that pathetic bird. A species described from Senegal in 1987 is already nearly extinct. This genus of plants is still largely ignored by scientists; precious little is known about its anatomy, chemical con- stituents, molecular relationships, and ecological interactions. By the time scientists get around to studying Pandanus, many of its species will be gone forever. Pandanus trees are tough but are no match for the bulldozer or the torch.

Pandanus is a remarkable genus of plants to which the modern world has not always been kind. It deserves better. So the next time you find yourself by Pandanus Lake, take a moment to appreciate the plants that lend their name to that lake. Pay your respects, make amends, or simply get to know these amazing plants.

Garden Views Summer 2002