The Fairchild Herbarium: More than just dead plants

Laurn Raz, Ph.D.

The world's major botanical gardens have herbaria as part of their research facilities. They are libraries of plant samp1es that provide essential information for research.

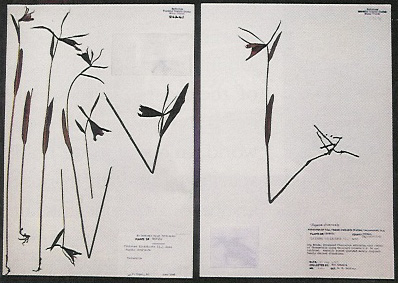

Herbarium specimens are vital references, they provide a physical reference (a voucher) for plant identification and studies of plant distribution, they provide an historical perspective (for instance a specimen may show a plant was once present in a reserve where it is now extinct), in addition herbarium specimens can be used for biochemical, anatomical and increasingly genetic research. Individually, each herbarium specimen is a record of a plant's existence in both space and time. There is almost no end to what we can do with herbarium spec1tnens, if we conserve them properly. Using the locality data from specimen labels, we can reconstruct entire floras (such as the Flora of Florida) or make detailed maps of species distributions that can be used for conservation assessments. Applications include monitoring of endangered species, identification of traded plant material and tracking introductions of exotic species. Beyond their applications for research, herbarium specimens are also used for teaching, creating displays for public education, and as the inspiration for countless botanical illustrations and paintings.

Most collections are housed in natural history museums, university biology departments or at botanic research institutions such as Fairchild. Typically, specimens are stored in airtight metal cabinets that protect them from light, heat and humidity. Properly curated and protected from insect and environmental damage, a specimen can last for hundreds of years (see fig 2). The oldest herbarium specimens are approaching five hundred years old!

Why does Fairchild need a collection of dried plants? Because Fairchild is a world-class research institution, and the Herbarium is at the core of many of our research programs. Simply stated, it is a source for our botanical conservation work — a place where our collections and their associated information can be held. We hold voucher specimens from our field expeditions and garden collections. For instance we have ca. 3,300 palm specimens, representing 710 species from around the world. This is one of the most important palm herbarium collections in the world. In addition we hold specimens on loan from other institutions that we consult for our research. For instance, we have large collections of the plant family, the Myrsinaceae, the subject of John Pipoly's research in the tropical forests of New Guinea and the Caribbean.

Herbarium specimens provide insight into geopolitical history and illuminate our own botanical history. We routinely consult material dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries, a period when Western explorers were mapping out the interiors of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Pressed plant specimens were routinely collected for identification and further study. Expeditions led by renowned explorers such as Alexander van Humboldt, and Lewis & Clark yielded many botarucal discoveries of species new to science. The Caribbean region in particular was one of the first regions to be intensively explored by European naturalists and some of the oldest scientific names (Latin binomials) in use today are of plants found in the Caribbean islands. The original specimens still exist and are deposited in herbaria around the world. In rare instances, the specimens are all we have left, as some species are feared extinct. This work continues today as Fairchild scientists continue to document the tropical world and find new species.

The technology for making herbarium specimens has not changed much in the last three hundred years. In fact, if you have ever pressed a flower in a book the technique may already be familiar to you. The difference is that instead of books, we use wooden boards and straps to create the pressure. And instead of the leaves of a book, specimens are separated by sheets of newspaper and sections of cardboard. In the field, specimens are collected (with permission!) using simple tools such as pruners and shovels. Hundredds of specimens can be sandwiched together into a single “plant press”. To dry the specimens, heat from the sun or from a gas or electrical source, is applied to the press until all the water evaporates between the airspaces of the cardboard.

Back in our Herbarium workroom, we prepare these pressed specimens for archival preservation. To accomplish this, we rely on a small army of dedicated volunteers. First the collection data is transcribed from field notebooks into a database to generate printed labels. The specimen and its corresponding label are then affixed with glue to a standard sized sheet of archival paper (Fig 3). The specimen may be also reinforced with a few stitches of thread. The mounted specimens are then assigned accession numbers, by which we keep track of our inventory, and the specimens are filed in our collection. The specimens are arranged in alphabetical order by plant family.

New specimens come in from staff-led expeditions, and also from exchange programs with other herbaria around the world. Growth also comes from mergers and acquisitions, like in business. Most recently, we inherited two large collections from the University of Miami, and from Florida Atlantic University, which shed their herbaria when they restructured their biology departments. Increasingly, botanical gardens such as Fairchild are taking on important and historical collections that universities and state facilities can no longer sustain. We have early 20th C. collections of John Kunkel Small, one of the most important figures in Florida botany; we also have 19th C. material from Florida collectors F. Rugel and A. H. Curtiss, and historical material from the Everglades. One of our most important collections is the original set of Correll vouchers which served as the basis for the widely acclaimed Flora of the Bahama Archipelago (1982).

With a total inventory of about 165,000 specimens (and growing) Fairchild is considered a medium-sized herbarium. Globally, there are more than 3,240 herbaria in 165 countries, and together these collections represent all of the known plant diversity on earth. Herbaria range in size from a few thousand to 7.5 million specimens. The largest Is at the Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle, in Paris. Our Herbarium focuses on the plants of Florida, the West Indies (Caribbean islands), and cultivated plants of the tropics. Fairchild is also one of the premier institutions of the world for palm research, and in support of our Palm Biology program, we curate palm specimens from all over the world. Within these areas of concentration, our specimens document variation at all levels of plant diversity, which include species, genus, family, order, etc., from the Linnaean hierarchy that you learned in high school! It is ideal to have multiple specimens of each species in order to appreciate the spectrum of variation that occurs within species.

In addition to our general collection, we also maintain a collection of Type specimens. A physical specimen must support all published plant names; the specimen that supports the name is called the TYPE. Many Types date back to the historical expeditions I mentioned earlier, although new species ate being described on a continual basis. Type specimens are deposited in herbaria around the world, and researchers may request to see them in person, or arrange to have them shipped on loan. The ability to see original material enables us to verify or refute direct observations that were made up to hundreds of years ago. This adds rigor to our field studies and makes Type specimens especially valuable. At Fairchild we have approximately 200 Types, including new specimens described by Fairchild scientists.

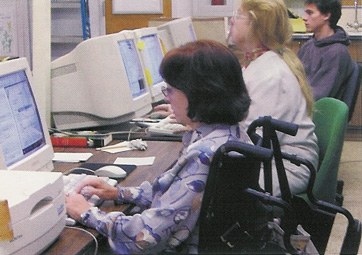

In 1999, Fairchild began a long-term initiative to put our entire Herbarium collection online. Currently we have over 46,000 specimens databased and linked to digital images that are searchable on the web. Almost a1l of the scanning (fig 4) and databasing (fig 5) has been done by our wonderful volunteers, whose work is supervised by Fairchild staff member Lynka Woodbury. Their collective efforts make our Herbarium accessible to people who would not otherwise be able to get to Miami,or who cannot afford the significant cost of shipping specimens on loan. At the present time, we have most of our Florida collection online, and the next phase of our operation is to digitize our Caribbean collections.

The Fairchild Herbarium is not open to the public, but we can arrange special tours for classes, or other educational groups. Scientific visitors are admitted by appointment. All of you are welcome to visit our Virtual Herbarium at anytime. Come see us at www:virtualherbarium.org.