The Relationship of Biogeography to Phylogeny

G.F. Guala

First Some History

Over the past two centuries Biogeography has evolved along with

other sciences from the descriptive age into the age of hypothesis testing.

Many hypotheses have been proposed and used over theyears.

They represent some of the "rules" that biogeographers have traditionally

and somewhat niavely followed over the years.

The "Centers of Origin" question that

was once central in Biogeography.

Now that we know that habitats move (habitat plates), the center of

origin for any group is a moving target and cannot really provide the kind

of spatial predictive answers that were once thought possible.

A widely used example

Hennig's Progression Rule

(Primitive forms at the base of the tree and the center of origin)

An early fully integrated (and flawed) system

Croizat's Panbiogeography

Tracks, Generalized Tracks and ancient connections (often Land Bridges).

Time scale issues and assumptions of non-existent, static (only endemics),

or linear evolution and static continents.

Lack of long distance dispersal

Vicariance Biogeography

Nelson & Platnick (also Wiley and Rosen)

-

The cladogram shows relative times of divergence of different clades.

-

We have an assumption of vicariant (or mimic vicariant) speciation.

-

Thus, the biogeographic pattern of radiation should follow the cladistic

pattern and be mappable to vicariant plates.

Strengths:

-

Predictive and testable in some instances.

-

It often actually works, especially for very old groups.

-

Its success helped convince the world of plate tectonics and their effect

on evolution.

-

It has contributed a rigorous paradigm for analyses.

Problems:

-

You need an independant hypothesis of geographic movements.

-

Rarely testable.

-

Generally there is no null, if the pattern doesn't fit, you assume dispersal,

if it does you assume vicariance.

-

Dispersal and extinction are major confounding forces.

-

Widespread and overlapping species distributions are very difficult to

interpret.

-

"areas" are difficult to define and prone to circularity.

An obligate equitorial group. Because, South America remained

connected to Australia through Antarctica later than it did to Africa one

might hypothesize a different area cladogram, but we are concerned with

a latitude limited group here so the austral connection was non-functional

as a corridor. The dispersal and climatic needs of the study organism

must be considered even in the independant cladogram used to test the area

cladogram.

The time scale issue.

If a vicariant event occurred for one species, then it is likely that

the entire community present at the time was effected. Thus, one

should see a biogeographic pattern across multiple taxa.

Exactly which taxa should we see it in (community assemblages)?

What if no speciation happened? What if we have extinction?

With the foundation of Vicariance Biogeography technique as well

as the extraordinarily useful and simple optimization algorithms available

now, we can apply all of the data to the cladogram and really, for the

first time, rigorously explore the relationships of habitats, traits

and areas to taxa.

If Vicariance Biogeography explores the relation of taxa to areas, Historical

Biogeography and Historical Ecology explore the relationships of taxa to

everything (including areas).

You can hang anything on a cladogram.

Because a cladogram is a representation of relative relationships and

not a complete phylogeny, it can be used as a framework on which to test

hypotheses of evolutionary directionality or series.

For example, Consider the following two hypotheses derived independently

of phylogenetic analyses:

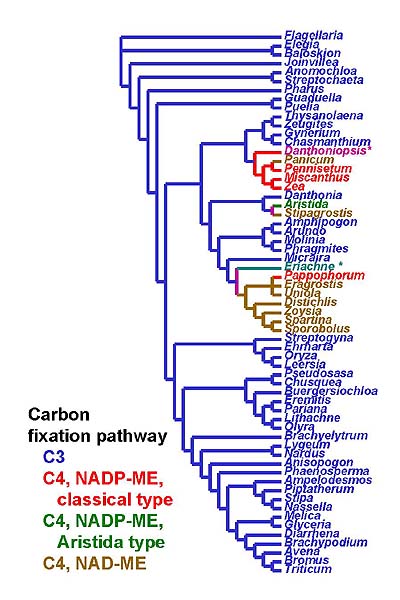

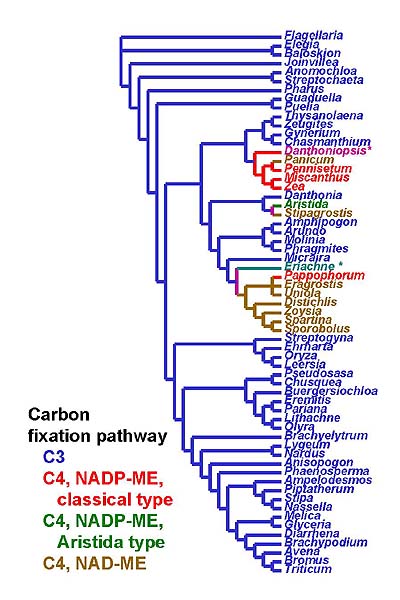

1. The C4 Carbon fixation pathway is much more complex and efficient

and therefore must have evolved from the C3 pathway.

2. The C4 Carbon fixation pathway is a very complex (and therefore unlikely)

evolutionary shift and must have therefore evolved only once.

Using a cladogram generated by the Grass Phylogeny Working Group

(1998) we can test these hypotheses.

We can see that the first hypothesis is supported and the second is

rejected.

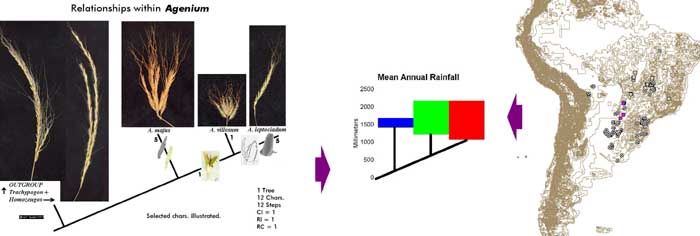

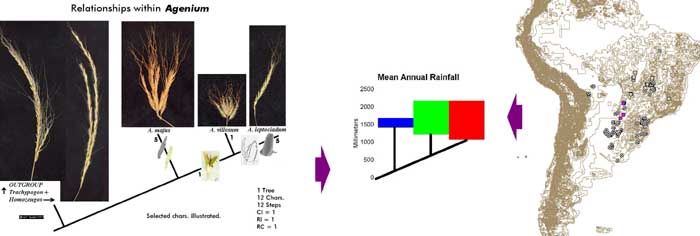

Historical Biogeography

We can test biogeographic hypotheses in the same way.

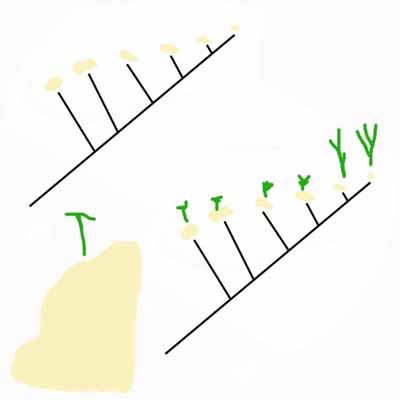

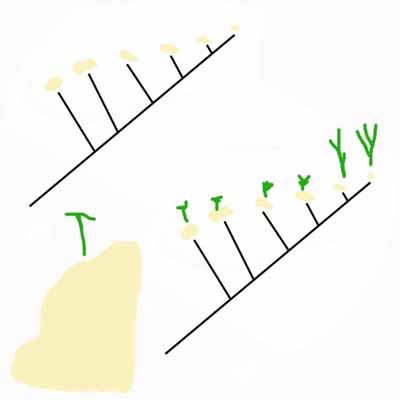

A simple archipelago example.

A climate example.