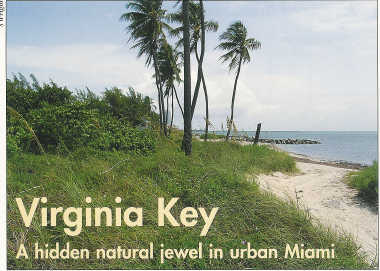

Virginia Key

Samuel J. Wright, Field Biologist/GIS Technician

Location of Jacquemontia reclinata seed germination/outplanting experiment

Imagine getting out of your car and taking a five-minute walk through such rare habitats as coastal dunes, coastal hammocks and mangroves. Could you envision a pleasant, relaxing day with a beach all to yourself in the middle of Miami? Come and lose yourself as you stroll through the Virginia Key Coastal Hammock Interpretive Trail at Virginia Key. With all of its diverse flora, fauna and cultural history, Virginia Key has a lot to offer.

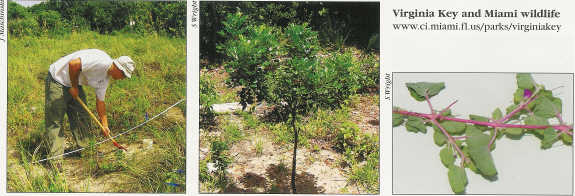

The Virginia Key Hammock is home to several rare South Florida plant species that Fairchild Tropical Garden biologists are currently researching. One of these endangered plant species is Okenia hypogaea. Recently a new, separate population was discovered by Wendy Teas, Sea Turtle Stranding Coordinator for the National Marine Fisheries Service. This separate population has pink pigment on the stems and leaf venation, a coloration that has never been observed in any other population. Also, a new population of Cyperus pedunculatus beach star was discovered by the Garden's Conservation intern, Allison Rosenberg. C. pedunculatus has never been documented on Virginia Key before. Research biologists from Fairchild are also conducting a seed germination / reintroduction experiment along the dune habitat with jacquemontia reclinata (beach clustervine). Virginia Key was determined suitable for J. reclinata reintroduction during a 2002 Fairchild Tropical Garden coastal area survey. The site ranked second among 29 coastal natural areas in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach Counties.

| |

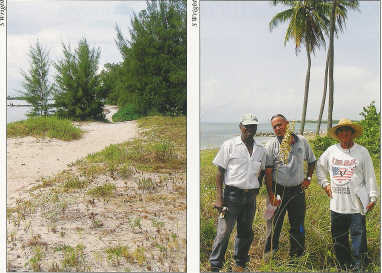

| Newly documented population of Cyperus pedunculatus (beach star) on Virginia Key discovered by Garden intern Allison Rosenberg | City of Miami Virginia Key Hammock Restoration crew (l to r): Reynaud Raymond, Juan Fernandez, Felipe Alonso. (not pictured: L. Zuaznabar) |

Before, and even more so after Hurricane Andrew (1992), Virginia Key Hammock was a barren area, low in plant diversity and infested by exotics such as Casuarina equisetifolia (Australian pine), Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper) and Colubrina asiatica (latherleaf). Over 60% of the area was covered by these invasive pest plants. After the storm, the City of Miami received funding to restore a l5-acre hammock damaged by the hurricane. The reforestation project has been spearheaded by the hard work and perseverance of park naturalist Juan Fernandez and his dedicated crew (opposite, top right). Exotics were removed and areas were replanted with natives. Removal of exotics resulted in an unexpected surprise. Before the initial exotic removal, there was only one known plant of the state endangered Zanthoxylum coriaceum (Biscayne prickly-ash) on Virginia Key. Within a short time of the removal, more than 40 individual prickly-ash plants were discovered. Later, seeds were collected from the mature plants of the population and used to repopulate the hammock. Fairchild staff has assisted in propagation of material used for outplantings. We have also collaborated with Virginia Key staff to map the population and monitor for survival.

| ||

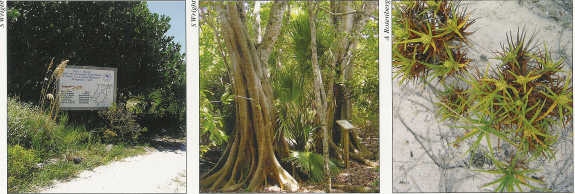

| Entrance to Virginia Key Hammock Interpretive Trail | Ficus aurea (Strangler fig) along the mature hammock trail portion of the interpretive trail | Flowering Cyperus pedunculatus (beach star) |

Wildlife enthusiasts will find Virginia Key Hammock particularly enjoyable. With the exotics reduced, the area provides suitable habitat for numerous species of butterflies that include zebra longwings (Heliconius charitonius), Julias (Dryas Julia), Gulf fritillaries (Agraulis vanillae), and giant swallowtails (Heraclides aristodemus). Migrating birds such as the pine siskin (Carduelis pinus), Tennessee warbler (Vermivora peregrina), Swainson's thrush (Catharus ustulatus), and indigo bunting (Passerina cyanea) have begun to make Virginia Hammock a stop on their journeys (www.ci.miami.fl.us). Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretfa) also use the beach each year to make their nests. Healthy offshore grassbeds, where rich submerged vegetation such as turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), and shoal grass (Halodule wrightit) grow, offer a place for bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus ssp. latirostris) to forage.

| ||

| Fairchild researcher Samuel J. Wright installs J. reclinata in the seed germination/outplanting experimental plot. | An extremely healthy Zanthoxylum coriaceum (Biscayne prickly-ash) that was outplanted in 2001 | Newly discovered Virginia Key population of Okenia hypogaea (beach peanut) with unusual pink coloring |

Not only does the island of Virginia Key have ecological value, it also has great historical significance. An Indian settlement named Pueblo Ratones was located there, and, in 1838, the island was the site of one of the battles in the Seminole Wars. What is now known as Virginia Key Beach Park was used during World War II for training African American servicemen, who were not permitted to train on "whites-only" beaches. On August 1, 1945, a time when segregation still existed, Virginia Key Beach Park or "Bear's Cut" was designated as the only Miami-Dade County beach that allowed African Americans. Beachgoers had to arrive by ferry because the Rickenbacker Causeway was not built until 1949. The area is now being considered for inclusion into the National Park System as a civil rights park. The site has also been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

So whether you know it as Bear's Cut, Virginia Beach Park, Cayo Ratones or do not know it at all, I invite you to leave all your worries behind and take a quiet, peaceful walk in your own backyard on Virginia Key.

For more information see:

Fernandez, J. 1998.

"The Miracle Workers of Virginia Key: Restoring Natural Systems in City of Miami Parks."

The Palmetto. Volume 1:2

Garden Views Autumn 2003