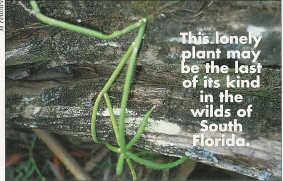

Log: Rhipsalis baccifera

Meghan Fellows, M.S., Former Field Biologist

Number of plants: 1

Number of Stems: 51-200

No Fruit(s)

No Flower(s)

Plant epiphytic, creeping, two stems pendulous

New stems with many spines; old stems without New growth; new death

GPS Position: yes

After slogging through thigh-deep water,swarmed by mosquitoes and threatened by poisonous snakes, a glimpse of an intriguing species is reward enough for Fairchild's botanists. Some of our more daring predecessors, including David Fairchild, have traveled to exotic locales like Borneo or Mauritius, but the South Florida plant conservation team finds our adventures here in our own backyard.

|

| Rhipsalis baccifera may be threatened by heavy winds, given it's precarious perch. |

Starting early from Coral Gables, Jennifer Possley and I set out once more to explore the unknown. This time we were after the elusive Rhipsalis baccifera, the pencil cactus, which has been part of the Garden's Center for Plant Conservation collection for ten years. This wide-spread cactus is found on every continent except Antarctica, the only cactus for which this is true. Distributed throughout the Caribbean and northern South America, the species reaches its far northern limits in South Florida. In the US, the cactus is currently known from only one location within Everglades National Park, discovered by Rob A. Campbell. There have been reports, some not confirmed since the 1970s, of other individual plants popping up here and there, especially in practically inaccessible places. On a previous trip we failed to find any plants further reminding us that there is a lot of wild space in the heart of the Everglades. But almost everyone was sure this specific plant was going to be right where we looked for it — if only we knew where to look.

|

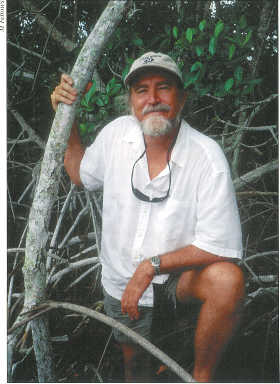

| Roger Hammer conjured the elusive plant, as if by magic |

That's where Roger Hammer comes into our story. People like Roger Hammer, Rob A. Campbell, George Gann and Keith Bradley have spent their lives exploring the wilds of South Florida, learning its secrets. As we journeyed into the Everglades by car, boat and foot, entertained by the flowering mangroves, jumping mullet and Roger's stories, we came to the spot where we thought the plant should be. Few have seen Rhipsalis baccifera recently, and we were about to find out if it is still around. This plant, perhaps the most endangered plant in the state, appeared magically, just as if Roger had conjured it from the depths of the mangroves.

|

| Meghan Fellows |

We have found that no matter where our work takes us, the plant we are searching for is not the only interesting plant. Here we saw skeletons of long-dead mangroves, some of which must have once been close to 80 feet tall, reminding us that these ecosystems were here before the beginnings of human history in this region, and, with luck, may outlast human occupation here. Encyclia tampensis, the common butterfly orchid, blooming in dazzling shades of red, pink and yellow, grew nearby. Phlebodium aureum, the golden polypody, made an appearance. Air plants (Tillandsia spp.) draped their leaves from overhanging branches, creating the mirage that many Rhipsalis were present, instead we had to be satisfied with just another incredible air plant. Harrisia simpsonii, (Simpson's prickly apple), Opuntia stricta (erect prickly pear) and Acanthocereus tetragonus (barbed-wire cactus) rounded out the cast of the Cactaceae family in this one location. Unfortunately most of the species we could see are listed as state threatened or endangered.

Exploring the ancient mangrove forests of South Florida is a rare treat, but one with a touch of sadness. How do we conserve a species when there is only one individual? Luckily, in the case of Rhipsalis, we have multiple individuals “in captivity” as part of our ex situ collection. Some of the ex situ collection is housed at the Garden, either in the Lynn Fort Lummus Garden or the Keys Coastal Habitat, while other plants grow away from the public eye. These plants are maintained with the hope that one day a suitable habitat may be found to establish a new population of Rhipsalis baccifera in South Florida.

There are three steps in conservation: protection, maintenance and restoration. As conservation biologists we are called upon to lend technical expertise in areas such as

- what to protect (how big? how much? what shape?)

- how to manage (should we prescribe a fire? or not?)

- how to restore (processes, systems and communities)

With these serious issues on my mind, I take one last look at what might be the last of its kind in the wilds of Florida, slap a mosquito, and begin the trek back to civilization.

This research is a collaborative product with Jennifer Possley; M.S., GIS Technician/Field Biologist.

It is funded by a grant "Conservation of South Florida Endangered and Threatened Flora"

from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Garden Views Autumn 2002